SECTION II

WALL STREET FUNDS THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION

“You will have a revolution, a terrible revolution. What course it takes will depend much on what Mr. Rockefeller tells Mr. Hague to do. Mr. Rockefeller is a symbol of the American ruling class and Mr. Hague is a symbol of its political tools.”

Leon Trotsky, in New York Times, December 13, 1938. (Hague was a New Jersey politician)

“The S.S. Kristianiafjord left New York on March 26, 1917, Trotsky was aboard holding an American passport—a long with other revolutionaries, Wall Street financiers, and American Communists.

“Notably, Lincoln Steffens was on board en route to Russia at the specific invitation of Charles Richard Crane, a backer and former chairman of the Democratic Party’s finance committee. Charles Crane, vice president of the Crane Company, had organized the Westinghouse Company in Russia, was a member of the Root mission to Russia… Richard Crane, his son, was confidential assistant to then Secretary of State Robert Lansing.

Crane returned to the United States when the Bolshevik Revolution was completed and, although a private citizen, was given firsthand reports of the progress of the Bolshevik Revolution by the State Dept. for example, one December 11, 1917, is entitled “Copy of report on Maximalist uprising for Mr. Crane.” I have the honor to enclose herewith a copy of same [above report] with the request that it be sent for the confidential information of Mr. Charles R. Crane. It is assumed that the Department will have no objection to Mr. Crane seeing the report… U.S. State Dept. Decimal File, 861.00/1026

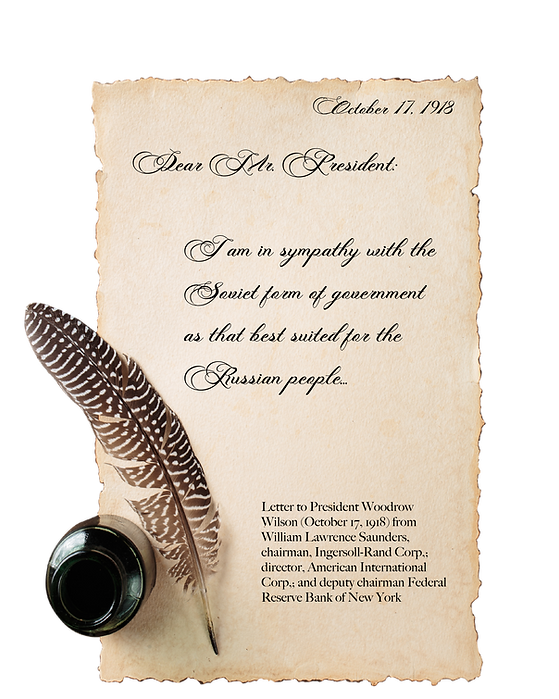

For the record: Trotsky’s passport was given to him by none other than President Woodrow Wilson. “Jennings C. Wise, in Woodrow Wilson: Disciple of Revolution, makes the pertinent comment, “Historians must never forget that Woodrow Wilson, despite the efforts of the British police, made it possible for Leon Trotsky to enter Russia with an American passport.”

Trotsky and company were detained in Halifax, Canada:

March 29, 1917, on orders from London via Halifax, the Trotsky party should be “taken off and retained pending instructions.” The reason given was, “these are Russian Socialists leaving for purposes of starting revolution against present Russian government for which Trotsky is reported to have $10,000 subscribed by Socialists and Germans.” Under pressure from the United States Government and Britain, Trotsky was to be released immediately. Dr. R.M. Coulter, Postmaster Genl. oversaw the release. Major General Gwatkin wrote Coulter on April 21, 1917, “Our friends the Russian socialists are to be released; and arrangements are being made for their passage to Europe.” The order to Captain Makins, Naval control officer at Halifax, for Trotsky’s release originated in the Admiralty, London. Coulter acknowledged the information, “which will please our New York correspondents immensely.”

Trotsky was released “at the request of the British Embassy at Washington… [which] acted on the request of the U.S. State Department, who were acting for someone else. Canadian officials were to inform the press that Trotsky was “an American citizen travelling on an American passport; that his release was specially demanded by the Washington State Department.” Moreover, writes MacLean, in Ottawa “Trotsky had, and continues to have, strong underground influence. There his power was so great that orders were issued that he must be given every consideration.” Macleon’s Magazine, 1918.

Lieutenant Colonel John Bayne MaClean, founder and president of MaClean Publishing Co., operated numerous Canadian trade journals, including the Financial Post. MaClean also had a long-time association with Canadian Army Intelligence. Sutton, Revolution. Pp. 21, 26, 31, 33-34

“It was not until the Bolsheviks had received from us a steady flow of funds through various channels and under varying labels that they were in a position to be able to build up their main organ, Pravda, to conduct energetic propaganda and appreciably to extend the originally narrow base of their party.”

Von Kuhlmann, minister of foreign affairs, to the Kaiser, December 3, 1917

Olof Aschberg, the “Bolshevik Banker,” was owner of the Nya Banken, founded 1912 in Stockholm. His codirectors included prominent members of Swedish cooperatives and Swedish socialists:

G.W. Dahl

K.G. Rosling

C. Gerhard Magnusson

Nya Banken was placed on a the Allied black list for it’s questionable operations in Germany. The name was changed to Svensk Ekonomiebolaget and remained under control of Aschberg. His London agent was the British Bank of North Commerce, whose chairman was Earl Grey, former associate of Cecil Rhodes. Others in Aschberg’s inner circle:

Krassin, (who emerged as a leading Bolshevik) ..... Russian manager of Siemens-Schukert in Petrograd

Carl Furstenberg ...... Minister of Finance for the first Bolshevik govt.

Max May ......... VP for foreign operations for Guaranty Trust of New York (J.P. Morgan)

In the summer of 1916 Aschberg was in New York on behave of Tsarist Russia to negotiate a $50 million dollar loan for Russia from National City Bank, (Rockefeller). That business concluded on June 5, 1916. Aschberg made some prophetic predictions regarding Russia while he was there:

“The opening for American capital and American initiative, with the awakening brought by the war, will be country-wide when the struggle is over. There are now many Americans in Petrograd, representatives of business firms, keeping in touch with the situation, and as soon as the change comes a huge American trade with Russia should spring up.” New York Times, August 4, 1916. Sutton, Revolution pp. 39, 57-58

Don’t’ forget John Dewey spoke of a new “world-wide market” in section I which the education system should support.

THE MONEY

WOLVES BEHIND THE MASK

“In 1918, the U.S. Senate conducted an investigation into the role played by prominent American citizens in supporting the Bolshevik’s rise to power. One of the documents entered into the record was an early communique from Robins to Bruce Lockhart. (Raymond Robins was an influential member of The American Red Cross Mission in Russia and Bruce Lockhart is the author of the book, British Agent, copyright 1933). In it Robins said:

“You will hear it said that I am an agent of Wall Street; that I am the servant of William B. Thompson to get Atlai Copper for him; that I have already got 500,000 acres of the best timber land in Russia for myself; that I have already copped off the Trans-Siberian Railway; that they have given me a monopoly of the platinum in Russia; that this explains my working for the soviet…. You will hear that talk. Now, I do not think it is true, Commissioner, but let us assume it is true. Let us assume that I am here to capture Russia for Wall Street and American businessmen. Let us assume that you are a British wolf and I am an American wolf, and that when this war is over we are going to eat each other up for the Russian market; let us do so in perfectly frank, man fashion, but let us assume at the same time that we are fairly intelligent wolves, and that we know that if we do not hunt together in this hour the German wolf will eat us both up.” U.S. Congress, Senate, Bolshevik Propaganda, Subcommittee of the Committee on the Judiciary, 65th Congress, 1919, p. 802

Professor Sutton has placed all this into perspective. In the following passage, he is speaking specifically about William Thompson, but his remarks apply with equal force to Robins and all of the other financiers who were part of the Red Cross Mission in Russia.

“Thompson’s motives were primarily financial and commercial. Specifically, Thompson was interested in the Russian market, and how this market could be influenced, diverted, and captured for postwar exploitation by a Wall Street syndicate, or syndicates. Certainly, Thompson viewed Germany as an enemy, but less a political than an economic or a commercial enemy. German industry and German banking were the real enemy. To outwit Germany, Thompson would achieve his objective. In other words, Thompson was an American imperialist fighting against German imperialism, and this struggle was shrewdly recognized and exploited by Lenin and Trotsky…

Thompson was not a Bolshevik; he was not even pro-Bolshevik. Neither was he pro-Kerensky. Nor was he even pro-American. The overriding motivation was the capturing of the postwar Russian market. This was a commercial objective. Ideology could sway revolutionary operators like Kerensky, Trotsky, Lenin et al., but not financiers.” Sutton, Revolution, pp. 97-98

Did the wolves of the Round Table actually succeed in their goal? Did they, in fact, capture the surplus resources of Russia? The answer to that question will not be found in our history books (because we know who controls the education system via grant money from section one). It must be tracked down along the trail of subsequent events, and what we must look for is this. If the plan had not been successful, we would expect to find a decline of interest on the part of high finance, if not outright hostility. On the other hand, if it did succeed, we would expect to see not only continued support, but some evidence of profit taking by the investors, a payback for their efforts and their risk. With those footprints as our guide, let us turn now to an overview of what has actually happened since the Bolsheviks were assisted to power by the financial Round Table network.

ITEM: After the October Revolution, all the banks in Russia were taken over and “nationalized” by the Bolsheviks—except for one: the Petrograd branch of Rockefeller’s National City Bank.

ITEM: Heavy industry in Russia was also nationalized—except the Westinghouse plant, which had been established by Charles Crane, one of the dignitaries aboard the S.S. Kristianiafjord who had traveled to Russia with Trotsky to witness the re-revolution.

ITEM: in 1922, the Soviets formed their first international bank. It was not owned and run by the state as would be dictated by Communist theory but was put together by a syndicate of private representatives of German, Swedish, and American banks. Most of the foreign capital came from England, including the British government itself.1 The man appointed as Director of the Foreign Division of the new bank was Max May, VP of Morgan’s Guaranty Trust Company in New York.

ITEM: in the years immediately following the October Revolution, there was a steady stream of large and lucrative (read non-competitive) contracts issued by the Soviets to British and American businesses which were directly or indirectly run by the financial Round Table network. The largest of these, for example, was a contract for fifty million pounds of food products to Morris & Company, Chicago meat packers. Edward Morris was married to Helen Swift, whose brother was Harold Swift. Harold Swift had been a “Major” at the Red Cross Mission in Russia.

ITEM: in payment for these contracts and to return the “loans” of the financiers, the Bolsheviks all but drained their country of its gold—which included the Tsarist government’s sizable reserve—and shipped it primarily to American and British banks. In 1920 alone, one shipment came to the U.S. through Stockholm valued at 39,000,000 Swedish kroner; three shipments came direct involving 540 boxes of gold valued at 97,200,000 gold rubles; plus at least one other direct shipment bringing the total to about $20 million. (Remember these are 1920 values!) The arrival of these shipments was coordinated by Jacob Schiff’s Kuhn, Loeb & Company and deposited by Morgan’s Guaranty Trust.2

ITEM: It was at about that time the Wilson Administration sent 700,000 tons of food to the Soviet Union which, not only saved the regime from certain collapse, but gave Lenin the power to consolidate his control over all of Russia.3 The U.S. Food Administration, which handled this giant operation, was handsomely profitable for those commercial enterprises that participated. It was headed by Herbert Hoover and directed by Lewis Lichtenstein Strauss, married to Alice Hanauer, daughter of one of the partners of Kuhn, Loeb & Company.

ITEM: U.S., British, and German wolves soon found a bonanza of profit in selling to the new Soviet regime. Standard Oil and General Electric supplied $37 million worth of machinery from 1921 to 1925, and that was just the beginning. Junkers Aircraft in Germany literally created Soviet air power. At least three million slave laborers perished in the icy mines of Siberia digging ore for Britain’s Lena Goldfields, Ltd. W. Averell Harriman—a railroad magnate and banker from the U.S. who later was to become Ambassador to Russia—acquired a twenty-year monopoly over all Soviet manganese production. Armand Hammer—close personal friend of Lenin—made one of the world’s greatest fortunes by mining Russian asbestos.” The Creature from Jekyll Island by G. Edward Griffin. Chapter III, The Best Enemy Money Can Buy, pp. 290-293.

-

George F. Kennan, The Decision to Intervene: Soviet-American Relations, 1917-1920 (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1958), pp. 190,235.

-

Bullard ms., U.S. State Dept. Decimal File, 316-11 – 1265, March 19, 1918.

The American Red Cross Mission in Russia, 1917

“The Red Cross mission as a cover for the Wall Street financiers

Formation of the Red Cross War Council

The Wall Street project in Russia in 1917 used the Red Cross Mission as its operational vehicle. Both Guaranty Trust and National City Bank had representatives in Russia at the time of the revolution. Frederick M. Corse of the National City Bank branch in Petrograd was attached to the American Red Cross Mission, of which a great deal will be said later. Guaranty Trust was represented by Henry Crosby Emery. Emery was temporarily held by the Germans in 1918 and then moved on to represent Guaranty Trust in China.

Up to about 1915 the most influential person in the American Red Cross National Headquarters in Washington, D.C. was Miss Mabel Boardman. An active and energetic promoter, Miss Boardman had been the moving force behind the Red Cross enterprise, although its endowment came from wealthy and prominent persons including J.P. Morgan, Mrs. E.H. Harriman, Cleveland H. Dodge, and Mrs. Russell Sage. The 1910 fund-raising campaign for $2 million, for example, was successful only because it was supported by these wealthy residents of New York City. In fact, most of the money came from New York City. J.P. Morgan himself contributed $100,000 and seven other contributors in New York City amassed $300,000. Only one person outside New York City contributed over $10,000 and that was William J. Boardman, Miss Boardman's father. Henry P. Davison was chairman of the 1910 New York Fund-Raising Committee and later became chairman of the War Council of the American Red Cross. In other words, in WWI the Red Cross depended heavily on Wall Street, and specifically on the Morgan firm.

The Red Cross was unable to cope with the demands of World War I and in effect was taken over by these New York bankers. According to John Foster Dulles, these businessmen "viewed the American Red Cross as a virtual arm of government, they envisaged making an incalculable contribution to the winning of the war."[1] In so doing they made a mockery of the Red Cross motto: "Neutrality and Humanity."

In exchange for raising funds, Wall Street asked for the Red Cross War Council; and on the recommendation of Cleveland H. Dodge, one of Woodrow Wison’s financial backers, Henry P. Davison, a partner in J.P. Morgan Company, became chairman. The list of administrators of the Red Cross then began to take on the appearance of the New York Directory of Directors:

-

John D. Ryan, president of Anaconda Copper Company (see frontispiece)

-

George W. Hill, president of the American Tobacco Company

-

Grayson M.P. Murphy, vice president of the Guaranty Trust Company

-

Ivy Lee, public relations expert for the Rockefellers.

Harry Hopkins, later to achieve fame under President Roosevelt, became assistant to the general manager of the Red Cross in Washington, D.C.

The question of a Red Cross Mission to Russia came before the third meeting of this reconstructed War Council, which was held in the Red Cross Building, Washington, D.C., on Friday, May 29, 1917, at 11:00 A.M. Chairman Davison was deputed to explore the idea with Alexander Legge of the International Harvester Company. Subsequently International Harvester, which had considerable interests in Russia, provided $200,000 to assist financing the Russian mission. At a later meeting it was made known that William Boyce Thompson, director of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, had "offered to pay the entire expense of the commission"; this offer was accepted in a telegram: "Your desire to pay expenses of commission to Russia is very much appreciated and from our point of view very important." [2]

The members of the mission received no pay. All expenses were paid by William Boyce Thompson and the $200,000 from International Harvester was apparently used in Russia for political subsidies. We know from the files of the U.S. embassy in Petrograd that the U.S. Red Cross gave 4,000 rubles to Prince Lvoff, president of the Council of Ministers, for "relief of revolutionists" and 10,000 rubles in two payments to Kerensky for "relief of political refugees."

In August 1917 the American Red Cross Mission to Russia had only a nominal relationship with the American Red Cross and must truly have been the most unusual Red Cross Mission in history. All expenses, including those of the uniforms -- the members were all colonels, majors, captains, or lieutenants -- were paid out of the pocket of William Boyce Thompson. One contemporary observer dubbed the all-officer group an "Haytian Army":

The mission actually comprised only twenty-four (not forty), having military rank from lieutenant colonel down to lieutenant, and was supplemented by three orderlies, two motion-picture photographers, and two interpreters, without rank. Only five (out of twenty-four) were doctors; in addition, there were two medical researchers. The mission arrived by train in Petrograd via Siberia in August 1917. The five doctors and orderlies stayed one month, returning to the United States on September 11.

Dr. Frank Billings, nominal head of the mission and professor of medicine at the University of Chicago, was reported to be disgusted with the overtly political activities of the majority of the mission. The other medical men were:

-

William S. Thayer, professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University

-

D. J. McCarthy, Fellow of Phipps Institute for Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis, at Philadelphia

-

Henry C. Sherman, professor of food chemistry at Columbia University

-

C. E. A. Winslow, professor of bacteriology and hygiene at Yale Medical School

-

Wilbur E. Post, professor of medicine at Rush Medical College

-

Dr. Malcolm Grow, of the Medical Officers Reserve Corps of the U.S. Army

-

Orrin Wightman, professor of clinical medicine, New York Polyclinic Hospital

George C. Whipple was listed as professor of sanitary engineering at Harvard University but in fact was partner of the New York firm of Hazen, Whipple & Fuller, engineering consultants. This is significant because Malcolm Pirnie -- of whom more later -- was listed as an assistant sanitary engineer and employed as an engineer by Hazen, Whipple & Fuller.

The majority of the mission, as seen from the table, was made up of lawyers, financiers, and their assistants, from the New York financial district. The mission was financed by William Boyce Thompson, described in the official Red Cross circular as "Commissioner and Business Manager; Director, United States Federal Bank of New York." Thompson brought along Cornelius Kelleher, described as an attaché to the mission but actually secretary to Thompson and with the same address -- 14 Wall Street, New York City. Publicity for the mission was handled by Henry S. Brown, of the same address. Thomas Day Thacher was an attorney with Simpson, Thacher & Bartlett, a firm founded by his father, Thomas Thacher, in 1884 and prominently involved in railroad reorganization and mergers. Thomas as junior first worked for the family firm, became assistant U.S. attorney under Henry L. Stimson, and returned to the family firm in 1909. The young Thacher was a close friend of Felix Frankfurter and later became assistant to Raymond Robins, also on the Red Cross Mission. In 1925 he was appointed district judge under President Coolidge, became solicitor general under Herbert Hoover, and was a director of the William Boyce Thompson Institute.

Members from Wall Street financial community and their affiliations

Members from Wall Street financial community and their affiliations

Andrews (Liggett & Myers Tobacco)

Barr (Chase National Bank)

Brown (c/o William B. Thompson)

Cochran (McCann Co.)

Kelleher (c/o William B. Thompson)

Nicholson (Swirl & Co.)

Pirnie (Hazen, Whipple & Fuller)

Redfield (Stetson, Jennings & Russell)

Robins (mining promoter)

Swift (Swift & Co.)

Thacher (Simpson, Thacher & Bartlett)

Thompson (Federal Reserve Bank of N.Y.)

Wardwell (Stetson, Jennings & Russell)

Whipple (Hazen, Whipple & Fuller)

Corse (National City Bank)

Magnuson (recommended by confidential agent of Colonel Thompson)

• Medical doctors

Billings (doctor)

Grow (doctor)

McCarthy (medical research; doctor)

Post (doctor)

Sherman (food chemistry)

Thayer (doctor)

Wightman (medicine)

Winslow (hygiene)

• Orderlies, interpreters, etc.

Brooks (orderly)

Clark (orderly)

Rocchia (orderly)

Travis (movies)

Wyckoff (movies)

Hardy (justice)

Horn (transportation)

Alan Wardwell, also a deputy commissioner and secretary to the chairman, was a lawyer with the law firm of Stetson, Jennings & Russell of 15 Broad Street, New York City, and H. B. Redfield was law secretary to Wardwell. Major Wardwell was the son of William Thomas Wardwell, long-time treasurer of Standard Oil of New Jersey and Standard Oil of New York. The elder Wardwell was one of the signers of the famous Standard Oil Trust Agreement, a member of the committee to organize Red Cross activities in the Spanish American War, and a director of the Greenwich Savings Bank.

His son Alan was a director not only of Greenwich Savings, but also of Bank of New York and Trust Co. and the Georgian Manganese Company (along with W. Averell Harriman, a director of Guaranty Trust). In 1917 Alan Wardwell was affiliated with Stetson, Jennings & Russell and later joined Davis, Polk, Wardwell, Gardner & Read ( Frank L. Polk was acting Secretary of State during the Bolshevik Revolution period). The Senate Overman Committee noted that Wardwell was favorable to the Soviet regime although Poole, the State Department official on the spot, noted that "Major Wardwell has of all Americans the widest personal knowledge of the terror" (316-23-1449). In the 1920s Wardwell became active with the Russian-American Chamber of Commerce in promoting Soviet trade objectives.

The treasurer of the mission was James W. Andrews, auditor of Liggett & Myers Tobacco Company of St. Louis. Robert I. Barr, another member, was listed as a deputy commissioner; he was a vice president of Chase Securities Company (120 Broadway) and of the Chase National Bank. Listed as being in charge of advertising was William Cochran of 61 Broadway, New York City.

Raymond Robins, a mining promoter, was included as a deputy commissioner and described as "a social economist." Finally, the mission included two members of Swift & Company of Union Stockyards, Chicago. The Swifts have been previously mentioned as being connected with German espionage in the United States during World War I. Harold H. Swift, deputy commissioner, was assistant to the vice president of Swift & Company; William G. Nicholson was also with Swift & Company, Union Stockyards.

Two persons were unofficially added to the mission after it arrived in Petrograd: Frederick M. Corse, representative of the National City Bank in Petrograd; and Herbert A. Magnuson, who was "very highly recommended by John W. Finch, the confidential agent in China of Colonel William B. Thompson." [4]

Thompson in Kerensky's Russia

What then was the Red Cross Mission doing? Thompson certainly acquired a reputation for opulent living in Petrograd, but apparently he undertook only two major projects in Kerensky's Russia: support for an American propaganda program and support for the Russian Liberty Loan. Soon after arriving in Russia, Thompson met with Madame Breshko-Breshkovskaya and David Soskice, Kerensky's secretary, and agreed to contribute $2 million to a committee of popular education so that it could "have its own press and... engage a staff of lecturers, with cinematograph illustrations" (State Dept. decimal file 861.00/ 1032); this was for the propaganda purpose of urging Russia to continue in the war against Germany. According to Soskice, "a packet of 50,000 rubles" was given to Breshko-Breshkovskaya with the statement, "This is for you to expend according to your best judgment." A further 2,100,000 rubles were deposited into a current bank account.

A letter from J.P. Morgan (Jr.) to the State Department (861.51/190) confirms that Morgan cabled 425,000 rubles to Thompson at his request for the Russian Liberty Loan; J. P. also conveyed the interest of the Morgan firm regarding "the wisdom of making an individual subscription through Mr. Thompson" to the Russian Liberty Loan. These sums were transmitted through the National City Bank branch in Petrograd.

Of greater historical significance, however, was the assistance given to the Bolsheviks first by Thompson, then, after December 4, 1917, by Raymond Robins.

Thompson’s contribution to the Bolshevik cause was recorded in the contemporary American press. The Washington Post of February 2, 1918, carried the following paragraphs:

GIVES BOLSHEVIKI A MILLION

W. B. Thompson, Red Cross Donor, Believes Party Misrepresented. New York, Feb. 2 (1918).

William B. Thompson (chairman of the NY Federal Reserve), who was in Petrograd from July until November last, has made a personal contribution of $1,000,000 to the Bolsheviks for the purpose of spreading their doctrine in Germany and Austria.

Mr. Thompson had an opportunity to study Russian conditions as head of the American Red Cross Mission, expenses of which also were largely defrayed by his personal contributions. He believes that the Bolsheviks constitute the greatest power against Pro-Germanism in Russia and that their propaganda has been undermining the militarist regimes of the General Empires.

Mr. Thompson deprecates American criticism of the Bolsheviks. He believes they have been misrepresented and has made the financial contribution to the cause in the belief that it will be money well spent for the future of Russia as well as for the Allied cause.

Hermann Hagedorn's biography The Magnate: William Boyce Thompson and His Time (1869-1930) reproduces a photograph of a cablegram from J.P. Morgan Jr. in New York to William B. Thompson, "Care American Red Cross, Hotel Europe, Petrograd." The cable is date-stamped, showing it was received at Petrograd "8-Dek 1917" (8 December 1917), and reads:

New York Y757/5 24W5 Nil -- Your cable second received. We have paid National City Bank one million dollars as instructed -- Morgan.

The National City Bank branch in Petrograd (owned by Rockefeller) had been exempted from the Bolshevik nationalization decree -- the only foreign or domestic Russian bank to have been so exempted. Hagedorn says that this million dollars paid into Thompson's NCB account was used for "political purposes."

Socialist Mining Promoter Raymond Robins

William B. Thompson left Russia in early December 1917 to return home. He traveled via London, where, in company with Thomas Lamont of the J.P. Morgan firm, he visited Prime Minister Lloyd George, an episode we pick up in the next chapter. His deputy, Raymond Robins [9], was left in charge of the Red Cross Mission to Russia. The general impression that Colonel Robins presented in the subsequent months was not overlooked by the press. In the words of the Russian newspaper Russkoe Slovo, Robins "on the one hand represents American labor and on the other hand American capital, which is endeavoring through the Soviets to gain their Russian markets." [10]

Raymond Robins started life as the manager of a Florida phosphate company commissary. From this base he developed a kaolin deposit, then prospected Texas and the Indian territories in the late nineteenth century. Moving north to Alaska, Robins made a fortune in the Klondike gold rush. Then, for no observable reason, he switched to socialism and the reform movement. By 1912 he was an active member of Roosevelt's Progressive Party. He joined the 1917 American Red Cross Mission to Russia as a "social economist."

There is considerable evidence, including Robins' own statements, that his reformist social-good appeals were little more than covers for the acquisition of further power and wealth, reminiscent of Frederick Howe's suggestions in Confessions of a Monopolist. For example, in February 1918 Arthur Bullard was in Petrograd with the U.S. Committee on Public Information and engaged in writing a long memorandum for Colonel Edward House. This memorandum was given to Robins by Bullard for comments and criticism before transmission to House in Washington, D.C. Robins' very un-socialistic and imperialistic comments were to the effect that the manuscript was "uncommonly discriminating, far-seeing and well done," but that he had one or two reservations -- in particular, that recognition of the Bolsheviks was long overdue, that it should have been effected immediately, and that had the U.S. so recognized the Bolsheviks, "I believe that we would now be in control of the surplus resources of Russia and have control officers at all points on the frontier." [11]

This desire to gain "control of the surplus resources of Russia" was also obvious to Russians. Does this sound like a social reformer in the American Red Cross or a Wall Street mining promoter engaged in the practical exercise of imperialism?

In any event, Robins made no bones about his support for the Bolshevists. [12] Barely three weeks after the Bolshevik phase of the Revolution started, Robins cabled Davison at Red Cross headquarters: "Please urge upon the President the necessity of our continued intercourse with the Bolshevik Government." Interestingly, this cable was in reply to a cable instructing Robins that the "President desires the withholding of direct communications by representatives of the United States with the Bolshevik Government." [13]

Several State Department reports complained about the partisan nature of Robin’s activities. For example, on March 27, 1919, Harris, the American Consul at Vladivostok, commented on a long conversation he had had with Robins and protested gross inaccuracies in the latter's reporting. Harris wrote, "Robins stated to me that no German and Austrian prisoners of war had joined the Bolshevik army up to May 1918. Robbins knew this statement was absolutely false." Harris then proceeded to provide the details of evidence available to Robins. [14]

Harris concluded, "Robbins deliberately misstated facts concerning Russia at that time and he has been doing it ever since."

On returning to the United States in 1918, Robins continued his efforts on behalf of the Bolsheviks. When the files of the Soviet Bureau were seized by the Lusk Committee, it was found that Robins had had "considerable correspondence" with Ludwig Martens and other members of the bureau. One of the more interesting documents seized was a letter from Santeri Nuorteva (alias Alexander Nyberg), the first Soviet representative in the U.S., to "Comrade Cahan," editor of the New York Daily Forward. The letter called on the party faithful to prepare the way for Raymond Robins:

(To Daily) FORWARD July 6, 1918

Dear Comrade Cahan:

It is of the utmost importance that the Socialist press set up a clamor immediately that Col. Raymond Robins, who has just returned from Russia at the head of the Red Cross Mission, should be heard from in a public report to the American people. The danger of armed intervention has greatly increased. The reactionists are using the Czecho-Slovak adventure to bring about invasion. Robins has all the facts about this and about the situation in Russia generally. He takes our point of view.

I am enclosing copy of Call editorial which shows a general line of argument, also some facts about Czecho-Slovaks.

Fraternally,

PS&AU Santeri Nuorteva

The International Red Cross and Revolution

Unknown to its administrators, the Red Cross has been used from time to time as a vehicle or cover for revolutionary activities.

The use of Red Cross markings for unauthorized purposes is not uncommon. When Tsar Nicholas was moved from Petrograd to Tobolsk allegedly for his safety (although this direction was towards danger rather than safety), the train carried Japanese Red Cross placards. The State Department files contain examples of revolutionary activity under cover of Red Cross activities. For example, a Russian Red Cross official (Chelgajnov) was arrested in Holland in 1919 for revolutionary acts (316-21-107). During the Hungarian Bolshevik revolution in 1918, led by Bela Kun, Russian members of the Red Cross (or revolutionaries operating as members of the Russian Red Cross) were found in Vienna and Budapest.

In 1919 the U.S. ambassador in London cabled Washington startling news; through the British government he had learned that "several Americans who had arrived in this country in the uniform of the Red Cross and who stated that they were Bolsheviks . . . were proceeding through France to Switzerland to spread Bolshevik propaganda." The ambassador noted that about 400 American Red Cross people had arrived in London in November and December 1918; of that number one quarter returned to the United States and "the remainder insisted on proceeding to France." There was a later report on January 15, 1918, to the effect that an editor of a labor newspaper in London had been approached on three different occasions by three different American Red Cross officials who offered to take commissions to Bolsheviks in Germany. The editor had suggested to the U.S. embassy that it watch American Red Cross personnel. The U.S. State Department took these reports seriously and Polk cabled for names, stating, "If true, I consider it of the greatest importance" (861.00/3602 and /3627).

To summarize: the picture we form of the 1917 American Red Cross Mission to Russia is remote from one of neutral humanitarianism. The mission was in fact a mission of Wall Street financiers to influence and pave the way for control, through either Kerensky or the Bolshevik revolutionaries, of the Russian market and resources. No other explanation will explain the actions of the mission. However, neither Thompson nor Robins was a Bolshevik. Nor was either even a consistent socialist.

The writer is inclined to the interpretation that the socialist appeals of each man were covers for more prosaic objectives. Each man was intent upon the commercial; that is, each sought to use the political process in Russia for personal financial ends. Whether the Russian people wanted the Bolsheviks was of no concern. Whether the Bolshevik regime would act against the United States -- as it consistently did later -- was of no concern. The single overwhelming objective was to gain political and economic influence with the new regime, whatever its ideology. If William Boyce Thompson had acted alone, then his directorship of the Federal Reserve Bank (New York) would be inconsequential. However, the fact that his mission was dominated by representatives of Wall Street institutions raises a serious question -- in effect, whether the mission was a planned, premeditated operation by a Wall Street syndicate. This the reader will have to judge for himself, as the rest of the story unfolds.

So far, from section one, we know why the financiers of perpetual wars wanted to control the education system. Now that we’ve seen the implementation of the goals of the Socialists and Monopolists of “capturing the new Russian market,” or “the world-wide market” as John Dewey put it, we move into the birth of the Military Industrial Complex (MIC) in section III.

So far, from section one, we know why the financiers of perpetual wars wanted to control the education system and that is because the most valuable resource to control is the manpower. Without the manpower there is no mining, no lumber, no factory workers, and no new market to capture, and no MIC. Now that we’ve seen the implementation of the goals of the Socialists and Monopolists of “capturing the new Russian market,” or “the world-wide market” as John Dewey put it, we move into the birth of the Military Industrial Complex (MIC) in section III.